Joint ownership of property with friends has surged in popularity in Arizona, driven by skyrocketing real estate prices and the desire for shared investments in a state known for its booming housing market. As of 2025, with median home prices in Phoenix exceeding $450,000 and even higher in suburbs like Scottsdale, pooling resources allows friends to afford properties that might otherwise be out of reach. However, Arizona’s property laws present unique challenges and opportunities for non-family co-owners. Unlike married couples who benefit from community property rules, friends must navigate forms of ownership that emphasize individual rights, potential disputes, and careful titling. This comprehensive guide explores the basics of joint ownership in Arizona, delves into community property nuances for non-spouses, explains deed types and titling, outlines best practices, and highlights common legal pitfalls with strategies to avoid them. Drawing from Arizona Revised Statutes (ARS) Title 33 and expert insights, this article aims to empower friends to make informed decisions, ensuring their shared property venture is both rewarding and legally sound.

The Basics of Joint Ownership in Arizona

Arizona’s real property laws, primarily governed by ARS Title 33, allow multiple individuals to own property together, but the form of ownership dictates rights, responsibilities, and outcomes upon sale or death. For friends—defined as non-spouses or unrelated parties—the key forms are tenancy in common (TIC) and joint tenancy with right of survivorship (JTWROS). These differ from community property, which is reserved for married couples. Community property without survivorship is also an option but limited to spouses.

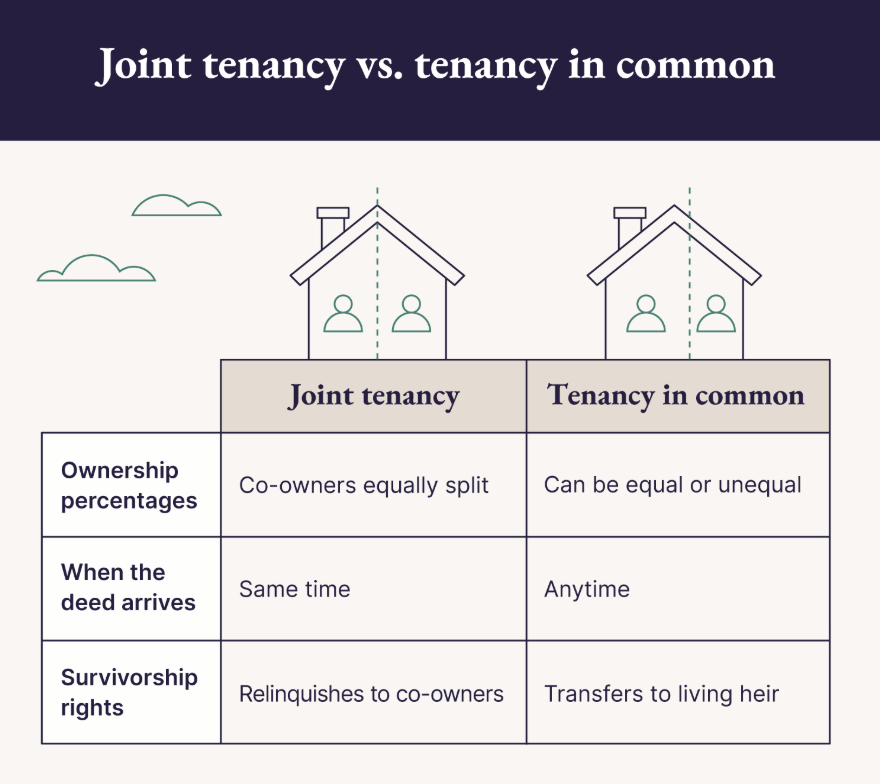

Tenancy in common is the default form when a deed transfers title to two or more people without specifying otherwise. In TIC, each co-owner holds an undivided interest in the entire property, meaning all have equal rights to use and possess it, regardless of share size. Shares can be unequal—for example, one friend might own 60% based on a larger down payment contribution, while others hold 20% each. This flexibility makes TIC ideal for friends with varying financial inputs. Importantly, there is no right of survivorship; upon a co-owner’s death, their share passes to their heirs via probate or a will, potentially introducing new, unintended co-owners like family members. Each owner can sell, gift, or encumber their share independently, but this can lead to complications if others disagree.

Joint tenancy with right of survivorship requires explicit language in the deed, such as “as joint tenants with right of survivorship.” It mandates equal shares and the “four unities”: unity of time (acquired simultaneously), title (from the same deed), interest (equal ownership), and possession (equal use rights). The defining feature is survivorship: when one owner dies, their share automatically transfers to the survivors, bypassing probate and simplifying inheritance. This can be advantageous for close friends seeking efficiency, but any owner can unilaterally sever the joint tenancy by conveying their interest, converting it to TIC. JTWROS is less flexible for unequal contributions, making it suitable only when equality and trust are paramount.

Arizona does not recognize tenancy by the entirety, a form available in some states that offers creditor protection for spouses. For friends, co-ownership can also occur through entities like limited liability companies (LLCs), which provide liability shields but may complicate financing and taxes. Regardless of form, all co-owners are jointly liable for property taxes, mortgages, and maintenance, though individual actions (like liens) typically affect only their share in TIC.

Community Property Nuances for Non-Married Co-Owners

Arizona is one of nine community property states, where assets acquired during marriage are presumed to be owned equally by spouses, regardless of title. However, these rules do not apply to non-married co-owners, including friends or unmarried partners. This creates significant nuances: without marriage, there’s no automatic 50/50 split or presumption of joint ownership for assets bought together. Instead, ownership defaults to separate property based on contributions, unless specified otherwise in a deed or agreement.

For friends, this means property purchased jointly is treated as TIC unless JTWROS is elected, with no community property protections like spousal consent for sales or creditor safeguards. Arizona does not recognize common-law marriage, so long-term cohabitation doesn’t confer community property rights. Domestic partners (registered under local ordinances in cities like Phoenix) may have limited rights, but for unrelated friends, these don’t apply.

A key nuance arises with mixed ownership: if a married person adds a friend to a deed for community property, it could complicate spousal rights, requiring the spouse’s consent to avoid claims of improper transfer. Friends should avoid titling as “community property,” as it’s invalid for non-spouses and could lead to court reinterpretation as TIC. Instead, use cohabitation or co-ownership agreements to mimic some community property benefits, such as defining asset division upon separation or death. These contracts can specify reimbursement for unequal contributions, like one friend paying more for improvements, preventing disputes over “separate” vs. “joint” claims.

In estate planning, non-married co-owners lack the survivorship default of community property with right of survivorship (available only to spouses since 1995). Friends must rely on JTWROS or trusts to achieve similar results. Tax implications differ too: community property offers a full step-up in basis upon a spouse’s death, but for friends in TIC or JTWROS, only the deceased’s share gets a step-up, potentially increasing capital gains taxes on sale. Consulting an attorney is crucial to navigate these nuances and ensure the arrangement aligns with Arizona’s separate property framework for non-spouses.

Deeds and Titling Property in Joint Ownership

Deeds are the legal instruments transferring property title in Arizona, and proper titling is essential for joint ownership with friends. Common deed types include warranty deeds (general or special), quitclaim deeds, and beneficiary deeds. Warranty deeds provide the strongest protections: a general warranty guarantees clear title against all claims, while a special warranty covers only defects during the seller’s ownership. Quitclaim deeds transfer interest without warranties, often used among friends for adding co-owners but risking title issues. Beneficiary deeds allow transfer on death, useful for avoiding probate in joint setups.

To establish joint ownership, the deed must specify the vesting. For TIC, it might read: “To A, B, and C as tenants in common with undivided interests of 50%, 30%, and 20%.” For JTWROS: “To A, B, and C as joint tenants with right of survivorship.” Omitting specifics defaults to TIC. Deeds must be notarized, recorded with the county recorder (e.g., Maricopa County for Phoenix), and include an affidavit of property value for tax purposes.

Friends should use a real estate attorney to draft deeds, ensuring compliance with ARS 33-401, which requires deeds to be in writing and describe the property accurately. Incorrect titling can lead to disputes; for instance, attempting community property vesting for non-spouses may be voided. Adding a friend to an existing deed via quitclaim can trigger reassessment for property taxes under Proposition 13-like rules in Arizona, increasing bills. Always verify title through a search to avoid liens or encumbrances.

Best Practices for Joint Ownership with Friends

Successful joint ownership requires proactive planning. First, select compatible co-owners with aligned financial goals and lifestyles. Discuss expectations openly: Will the property be a primary residence, vacation home, or investment? Next, draft a comprehensive co-ownership agreement, a binding contract outlining shares, cost-sharing (mortgage, taxes, repairs), usage rules, and exit strategies like buyouts or rights of first refusal. This agreement supplements the deed and can prevent disputes by addressing scenarios like one friend defaulting on payments.

Choose the right ownership form: TIC for flexibility, JTWROS for survivorship. For financing, apply jointly—lenders assess combined income and credit, but all are liable for the full mortgage. Maintain separate finances for personal contributions to avoid commingling, which could complicate separations. Schedule regular meetings to review expenses and property status, and consider mediation clauses for conflicts. Insure the property adequately, with policies reflecting ownership shares, and plan for taxes—Arizona has no state inheritance tax, but federal estate taxes may apply. Finally, consult professionals: a real estate attorney, financial advisor, and accountant to tailor the setup.

Avoiding Legal Pitfalls

Joint ownership pitfalls abound, but awareness and prevention strategies can mitigate them. A common issue is unequal contributions leading to resentment; avoid by documenting reimbursements in the agreement. Disputes over sales can trigger partition actions under ARS 12-1211, where a court orders division or forced sale, often at a loss after fees. Prevent this with buyout provisions.

Inheritance surprises occur in TIC when heirs inherit, disrupting the group; opt for JTWROS or beneficiary deeds. Creditor risks: one friend’s debts can lien their share, affecting the property; use LLCs for protection. Tax pitfalls include gift taxes on adding co-owners or reassessments; consult a tax expert. Relationship breakdowns can lead to costly litigation; include arbitration clauses. Finally, failing to update documents after life changes (e.g., marriage) can complicate matters; review annually.

Conclusion

Joint ownership with friends in Arizona offers affordability and camaraderie but demands vigilance under state laws favoring separate property for non-spouses. By understanding TIC, JTWROS, community property limitations, deed requirements, best practices, and pitfalls, friends can forge secure partnerships. Always seek legal counsel to customize your approach—turning potential risks into a solid foundation for shared success.